|

Chapter 6

Contents

The

PRC's Launch Failure Investigation

The

Asia Pacific Telecommunications Insurance Meeting

The

PRC's Creation of an 'Independent Review Committee'

The

Independent Review Committee's Meetings

The

Independent Review Committee's Report

Substance

of the Preliminary Report

The

Report Goes to the PRC

Defense

Department Analyst Discovers the Activities of the Independent Review

Committee

Loral

and Hughes Investigate the Matter

The

Aftermath: China Great Wall Industry Corporation Revises Its Findings on

the Cause of the Accident

U.S.

Government Assessments of the Independent Review Committee's Report, and

Referral to the Department of Justice

Background

on Intelsat and Loral

Intelsat

Loral

Space and Communications

Space

Systems/Loral

Intelsat

708 Launch Program

The

Intelsat 708 Launch Failure

Events

Leading Up to the Creation of the Independent Review

Committee

The

Government Security Committee Meeting at Loral

The

Apstar 1A Insurance Meeting

The

April 1996 Independent Review Committee Meetings in Palo

Alto

Meeting

on April 22, 1996

Meeting

on April 23, 1996

Meeting

on April 24, 1996

United

States Trade Representative Meeting on April 23, 1996

The

April and May 1996 Independent Review Committee Meetings in

Beijing

Meeting

on April 30, 1996

Members'

Caucus at the China World Hotel

Meeting

on May 1, 1996

The

Independent Review Committee Preliminary Report

Writing

the Report

Loral

Sends the Draft Report to the PRC

The

Contents of the Draft Report

Notification

to Loral Officials That a Report Had Been Prepared

Loral

Review and Analysis of the Independent Review Committee

Report

The

Final Preliminary Report is Sent to the PRC

Another

Copy of the Report is Sent to Beijing

Loral

Management Actions After Delivery of the Report

to the

PRC

Defense

Department Official Discovers the Activities of the Independent Review

Committee

Meeting

with the Defense Technology Security Administration

Meeting

with the State Department

Reynard's

Telephone Call to Loral

Loral

Management Discovers the Independent Review Committee Report Has Been

Sent to the PRC

Loral's

'Voluntary' Disclosure

Investigation

by Loral's Outside Counsel

Loral

Submits Its 'Voluntary' Disclosure to the State

Department

The

PRC Gives Its Final Failure Investigation Report

Assessments

By U.S. Government Agencies and Referral to the Department of

Justice

Defense

Department 1996 Assessment

Central

Intelligence Agency Assessment

Department

of State Assessment

Defense

Technology Security Administration 1997 Assessment

Interagency

Review Team Assessment

Outline

of What Was Transferred to the PRC

Independent

Review Committee Meeting Minutes

Independent

Review Committee Preliminary Report

Loral's

Inaccurate Instructions on Releasing Public Domain Information to

Foreigners

Instructions

to the Independent Review Committee Regarding Public Domain

Information

State

Department Views on Public Domain Information

The

Defense Department Concludes That the Independent Review Committee's

Work Is Likely to Lead to the Improved Reliability of PRC Ballistic

Missiles

The

Cross-Fertilization of the PRC's Rocket

and Missile Design

Programs

The

Independent Review Committee Aided the PRC in Identifying the Cause of

the Long March 3B Failure

The

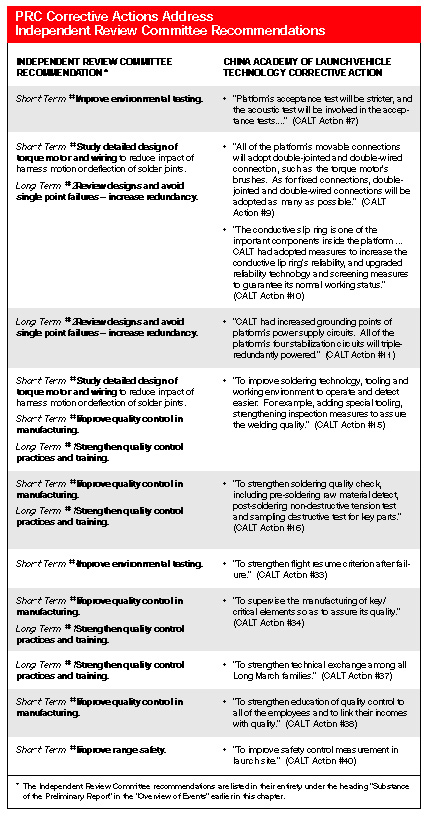

PRC Implemented All of the Independent Review Committee's

Recommendations

The

Independent Review Committee Helped the PRC Improve the Reliability of

Its Long March Rockets

Chapter 6

Summary

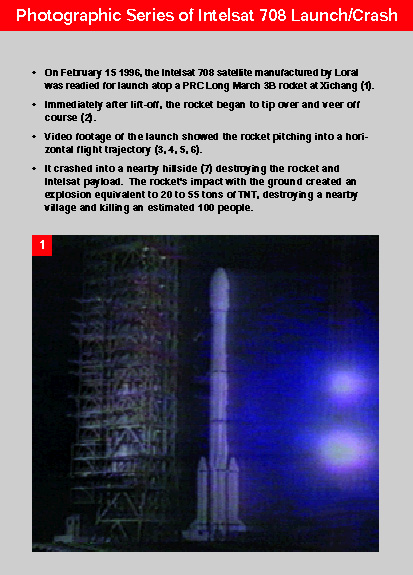

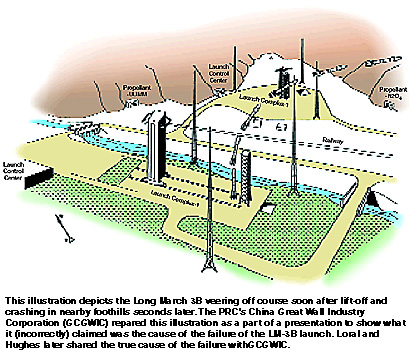

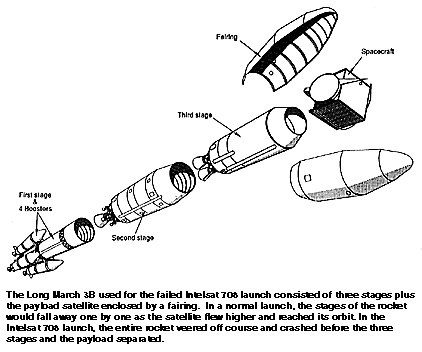

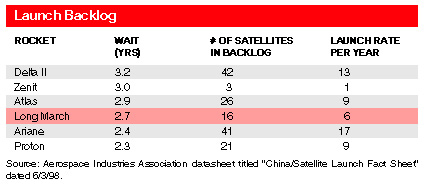

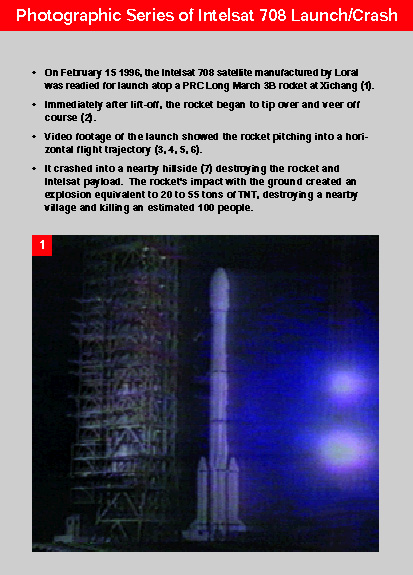

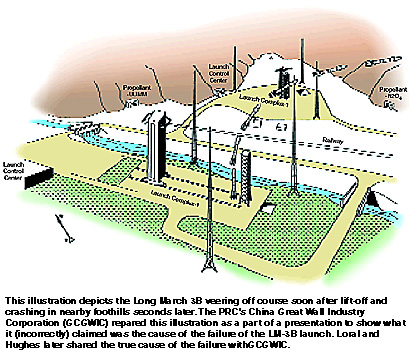

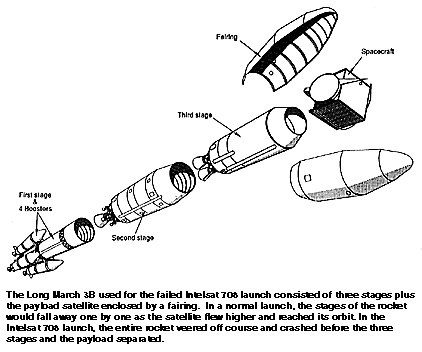

n February 15, 1996, a Long March 3B

rocket carrying the U.S.-built Intelsat 708 satellite crashed just

after lift off from the Xichang launch center in the People's Republic of

China. This was the third launch failure in 38 months involving the PRC's

Long March series of rockets carrying U.S.-built satellite payloads. It

also was the first commercial launch using the new Long March 3B. These

events attracted intense attention from the international space launch

insurance industry, and eventually led to a review of the PRC launch

failure investigation by Western aerospace engineers.

The activities of the Western aerospace engineers who participated

on the review team - the Independent Review Committee - sparked

allegations of violations of U.S. export control regulations. The

review team was accused of performing an unlicensed defense service for

the PRC that resulted in the improvement of the reliability of the PRC's

military rockets and ballistic missiles.

The Intelsat 708 satellite was manufactured by Space Systems/Loral

(Loral) under contract to Intelsat, the world's largest commercial

satellite communications services provider. Loral is wholly owned by

Loral Space & Communications, Ltd.

China Great Wall Industry Corporation, the PRC state-controlled

missile, rocket, and launch provider, began an investigation into the

launch failure. On February 27, 1996, China Great Wall Industry

Corporation reported its determination that the Long March 3B launch

failure was caused by a broken wire in the inner frame of the inertial

measurement unit within the guidance system of the rocket. In March 1996,

representatives of the space launch insurance industry insisted that China

Great Wall Industry Corporation arrange for an independent review of the

PRC failure investigation.

In early April 1996, China Great Wall Industry Corporation invited

Dr. Wah Lim, Loral's Senior Vice President and General Manager of

Engineering and Manufacturing, to chair an Independent Review Committee

that would review the PRC launch failure investigation. Lim then recruited

experts to participate in the Independent Review Committee: four senior

engineers from Loral, two from Hughes Space & Communications, one from

Daimler-Benz Aerospace, and retired experts from Intelsat, British

Aerospace, and General Dynamics.

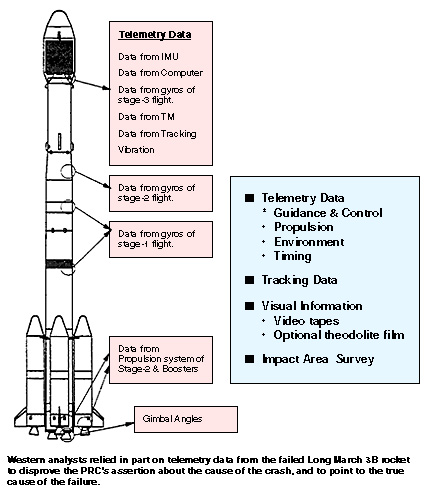

The Independent Review Committee members and staff met with PRC

engineers during meetings in Palo Alto, California, and in Beijing.

During these meetings the PRC presented design details of the Long March

3B inertial measurement unit, and the committee reviewed the failure

analysis performed by the PRC.

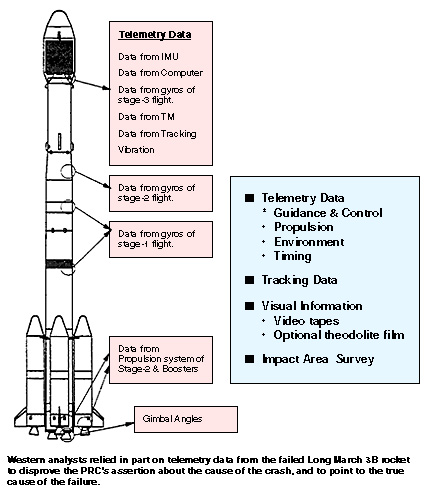

The Independent Review Committee took issue with the conclusions of

the PRC investigation because the PRC failed to sufficiently explain the

telemetry data obtained from the failed launch.

The Independent Review Committee members proceeded to generate a

Preliminary Report, which was transmitted to China Great Wall Industry

Corporation in May 1996 without prior review by any U.S. Government

authority. Before the Independent Review Committee's involvement, the

PRC team had concluded that the most probable cause of the failure was the

inner frame of the inertial measurement unit. The Independent Review

Committee's draft report that was sent to the PRC pointed out that the

failure could also be in two other places: the inertial measurement unit

follow-up frame, or an open loop in the feedback path. The Independent

Review Committee recommended that the PRC perform tests to prove or

disprove all three scenarios.

After receiving the Independent Review Committee's report, the PRC

engineers tested these scenarios and, as a result, ruled out its original

failure scenario. Instead, the PRC identified the follow-up frame as the

source of the failure. The PRC final report identified the power

amplifier in the follow-up frame to be the root cause of the failure.

According to the Department of Defense, the timeline and evidence

suggests that the Independent Review Committee very likely led the PRC to

discover the true failure of the Long March 3B guidance platform.

At the insistence of the State Department, both Loral and Hughes

submitted "voluntary" disclosures documenting their involvement in the

Independent Review Committee. In its disclosure, Loral stated that

"Space Systems/Loral personnel were acting in good faith and that harm to

U.S. interests appears to have been minimal." Hughes' disclosure concluded

that there was no unauthorized export as a result of the participation of

Hughes employees in the Independent Review Committee.

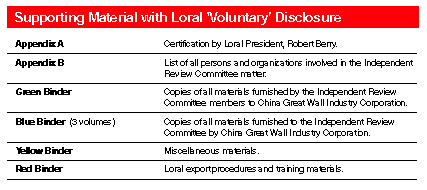

The materials submitted by both Loral and Hughes in their disclosures

to the State Department were reviewed by several U.S. government offices,

including the State Department, the Defense Technology Security

Administration, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and other Defense

Department agencies.

The Defense Department assessment concluded that "Loral and Hughes

committed a serious export control violation by virtue of having performed

a defense service without a license . . . "

The State Department referred the matter to the Department of

Justice for possible criminal prosecution.

The most recent review of the Independent Review Committee matter was

performed by an interagency review team in 1998 to reconcile differences

in the assessments of the other agencies. That interagency team

concluded:

� The actual cause of the Long

March 3B failure may have been discovered more quickly by the PRC as a

result of the Independent Review Committee report

� Advice given to the PRC by

the Independent Review Committee could reinforce or add vigor to the

PRC's design and test practices

� The Independent Review

Committee's advice could improve the reliability of the PRC's

rockets

� The technical issue of

greatest concern was the exposure of the PRC to Western diagnostic

processes, which could lead to improvements in reliability for all PRC

missile and rocket programs

Chapter 6

Text

INTELSAT 708 LAUNCH

FAILURE

LORAL

INVESTIGATION

PROVIDES PRC WITH

SENSITIVE INFORMATION

Overview of Events

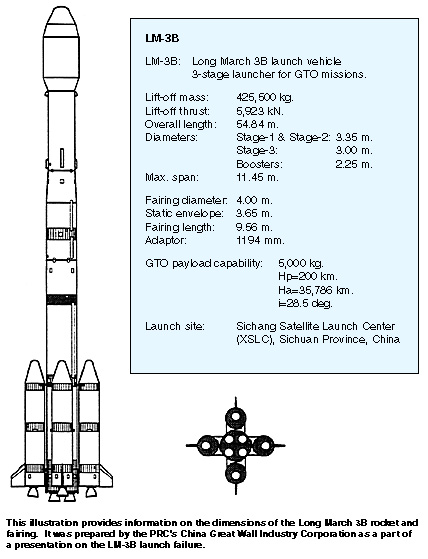

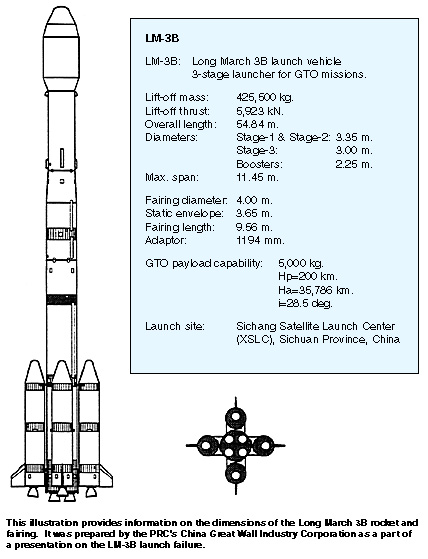

n February 15, 1996, the Intelsat 708 satellite

was launched on a Long March 3B rocket from the Xichang Satellite Launch

Center in the PRC.1 Even before clearing the launch tower, the rocket

tipped over and continued on a flight trajectory roughly parallel to the

ground.2 After only 22 seconds of flight, the rocket crashed into a nearby

hillside, destroying the rocket and the Intelsat satellite it carried.

The crash created an explosion that was roughly equivalent to 20 to 55

tons of TNT. It destroyed a nearby village. According to official PRC

reports, six people died in the explosion,3 but other accounts estimate

that 100 people died as a result of the crash.4

The Intelsat 708 satellite was manufactured by a U.S. company, Space

Systems/Loral (Loral), under contract to Intelsat, the world's largest

commercial satellite communications services provider.5 In October 1988,

Intelsat had awarded a contract to Loral to manufacture several satellites

in a program known as Intelsat VII. That contract had a total value of

nearly $1 billion.

Intelsat subsequently exercised an option under that contract for Loral

to supply four satellites - known as the Intelsat VIIA series - including

the Intelsat 708 satellite.6

In April 1992, Intelsat contracted with China Great Wall Industry

Corporation for the PRC state-owned company to launch the Intelsat VIIA

series of satellites into the proper orbit using PRC Long March rockets.7

Low price and "politics" were important factors in selecting the PRC

launch services.8

In March 1996, following the Intelsat 708 launch failure, Intelsat

terminated its agreement with China Great Wall Industry Corporation for

additional launch services.9

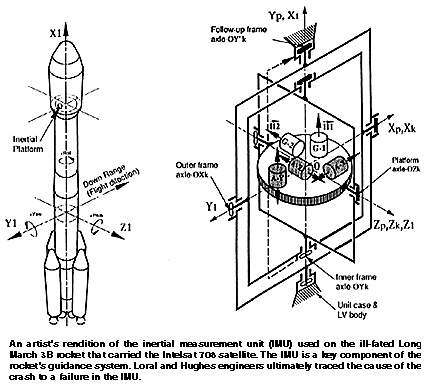

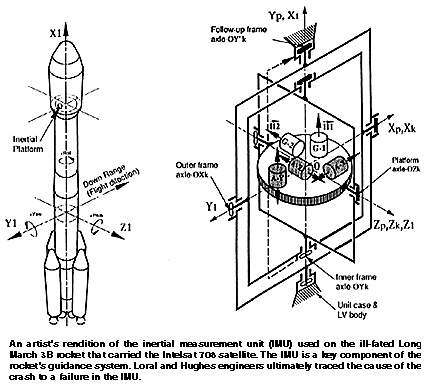

The PRC's

Launch Failure Investigation

China Great Wall Industry Corporation created two groups of PRC

nationals to investigate the launch failure. These were the Failure

Analysis Team and the Failure Investigative Committee. These two

committees reported to an Oversight Committee.

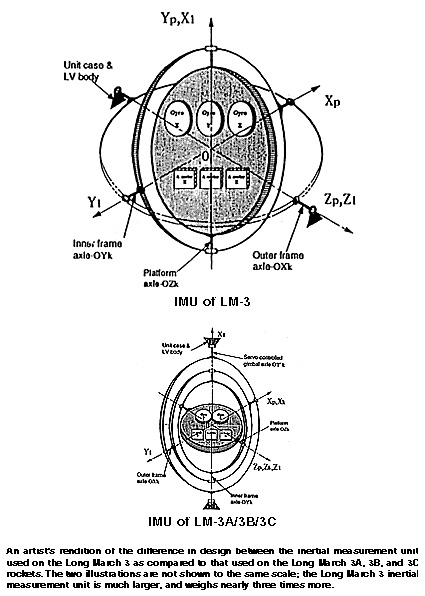

On February 27, 1996, China Great Wall Industry Corporation reported

its determination that the Long March 3B launch failure was caused by a

failure in the inertial measurement unit within the control system of the

rocket.10 The inertial measurement unit is a component that provides an

attitude reference for the rocket, basically telling it which way is

up.11

The Asia

Pacific Telecommunications Insurance Meeting

On March 14, 1996, a group of space launch insurance representatives

met in Beijing with representatives of Hughes, the PRC-controlled Asia

Pacific Telecommunications Satellite Co., Ltd., and China Great Wall

Industry Corporation. The purpose of the meeting was to examine the risks

associated with the upcoming launch of the Apstar 1A satellite that was

scheduled for July 3, 1996 on a Long March 3 rocket, in the wake of the

February 15 Long March 3B crash.12

The PRC assured those at the meeting that the launch was not at risk

because the Long March 3 rocket uses a different kind of inertial

measurement unit than the one that failed on the Long March 3B.13

At that meeting, Paul O'Connor, from the J&H Marsh & McLennan

insurance brokerage firm, reportedly insisted that the PRC do two things

before the space insurance industry would insure future launches from the

PRC: first, produce a final report on the cause of the Long March 3B

launch failure; and second, arrange for an independent review of the PRC

failure investigation.14

The PRC's

Creation of an 'Independent Review Committee'

In early April 1996, China Great Wall Industry Corporation invited both

Loral and Hughes Space & Communications (Hughes) to participate in an

Independent Review Committee that would review the PRC launch failure

investigation.15 The PRC then invited Dr. Wah Lim, Loral's Senior Vice

President and General Manager of Engineering and Manufacturing, to chair

the committee.16

Lim impaneled the Independent Review Committee with experts from Loral,

Hughes, and Daimler-Benz Aerospace, and retired experts from General

Dynamics, Intelsat, and British Aerospace.17

The

Independent Review Committee's Meetings

The Independent Review Committee held two sets of official meetings.18

The first set of meetings was from April 22 to 24, 1996, at Loral's

offices in Palo Alto, California.19 The second set of meetings was from

April 30 to May 1, 1996, in Beijing.20

At these meetings, the Independent Review Committee members reviewed

the extensive reports furnished by China Great Wall Industry Corporation

documenting the PRC launch failure investigation, and provided the PRC

with numerous technical questions regarding the material.21 The

committee's activities also included tours of PRC assembly and test

facilities for guidance and control equipment. The Independent Review

Committee members caucused at their hotel in Beijing on April 30 to

discuss and assess the PRC investigation privately.22

An aborted third round of Independent Review Committee meetings was

scheduled for June 1996. However, the U.S. Government issued a cease and

desist letter to both Loral and Hughes, ordering the companies to stop all

activity in connection with the failure review. The letter also requested

each company to disclose the facts related to, and circumstances

surrounding, the Independent Review Committee.23

The Independent Review Committee

activity was not authorized by any U.S. Government export license or

Technical Assistance Agreement.24 Loral had obtained two export licenses

(No. 533593 and No. 544724) from the State Department in 1992 and 1993 to

allow the launch of the Intelsat 708 satellite in the PRC. Neither of

those licenses authorized any launch failure investigative activity.25

Loral was aware from the start of the Independent Review Committee's

meetings that it did not have a license for the Independent Review

Committee activity.26

The Independent Review Committee meetings were not attended by any U.S.

Government monitors, as almost certainly would have been required had

there been an export control license.

The

Independent Review Committee's Report

Lim had promised the PRC that the Independent Review Committee would

report its preliminary findings by May 10, 1996.27 This deadline was

driven by Loral's need to determine, by that date, whether its Mabuhay

satellite would be launched on a PRC rocket as planned.

Following the meeting of the Independent Review Committee in Beijing,

the committee members collaborated by facsimile and e-mail to generate a

report of their findings. Loral engineer Nick Yen, who was the Secretary

for the Independent Review Committee, collected input from the committee

members and compiled the report. British committee member John Holt

drafted the technical section of the report, with inputs from the other

committee members.28

A draft of the Independent Review Committee Preliminary Report was

completed by May 7, 1996; the Preliminary Report was completed on May 9,

1996.

Substance of

the Preliminary Report

The Independent Review Committee's Preliminary Report was

approximately 200 pages in length. It comprised:

� Meeting minutes

� Independent Review Committee

questions and China Great Wall Industry Corporation answers

� Findings

� Short-term and long-term

recommendations

� The Independent Review

Committee charter and schedule

� The Independent Review

Committee membership roster

�

Appendices29

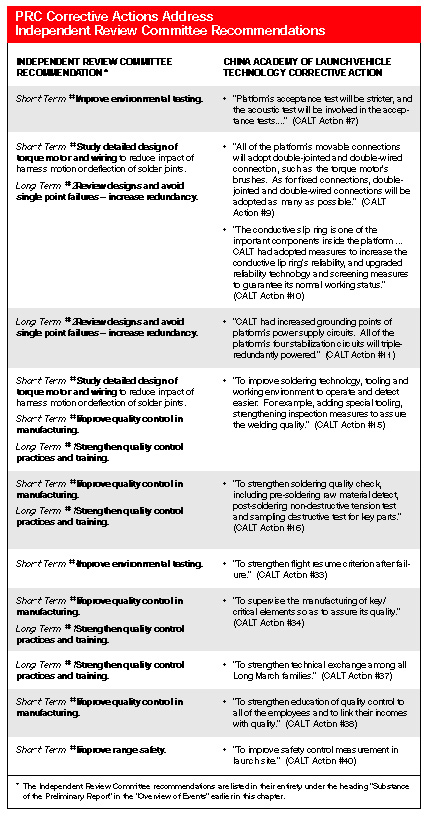

The thrust of the recommendations presented in the report was:

Short-Term Recommendations30

1) An explanation of the total flight behavior is essential to

fully confirm the failure mode. A mathematical numerical solution is

recommended immediately, to be followed by a hardware in-the-loop

simulation test when possible.

2) The detailed design of the motor and its wiring should be

studied to either: a) preclude harness motion during gimbal motion

or b) alleviate the impact of unavoidable deflection on solder joint

integrity.

3) Higher quality control and quality standards in the

manufacturing process need to be implemented and adhered to.

4) The China Academy of Launch Technology should re-examine the

environmental test plan for all avionics equipment. It is the

Independent Review Committee's opinion that the environmental tests

performed by the China Academy of Launch Technology might not be

adequate for meeting the requirements of the expected maximum flight

loads, including acoustic noises, or detecting the defects in the flight

hardware.

5) The Independent Review Committee is very concerned over the

range safety issues in the areas of operation safety, launch safety and

personal safety in general. Due to the difference in operations and

requirements by various customers/satellite contractors of China Great

Wall Industry Corporation, it is not suitable for the Independent Review

Committee to make generic recommendations for overall implementation

requirements. However, China Aerospace Corporation and China Great Wall

Industry Corporation should carefully review the Action Items, #19, #20,

and #21, of the first committee meeting and propose a well thought

implementation plan to be reviewed, agreed, and accepted by China Great

Wall Industry Corporation's individual customer/prime satellite

contractor.

Long-Term Recommendations31

1) Quality control philosophy and practice of the fabrication,

assembly and test of the inertial measurement unit should be

strengthened. Personnel should be trained periodically in careful

handling and cleanliness concerns. Cleanliness and careful test handling

should be emphasized and maintained at all times.

2) Good design and good quality control can achieve the desired

reliability of hardware. However, a design with adequate redundancy

can also achieve the same desired reliability. Therefore, it should be

strongly considered in avoiding critical single point (or path)

failure.

The Report

Goes to the PRC

On May 7, 1996, Loral's Nick Yen, the Secretary of the Independent

Review Committee, faxed the draft Preliminary Report to the committee

members, and to China Great Wall Industry Corporation.

On May 10, 1996, the final Independent Review Committee Preliminary

Report, less attachments, was faxed by Yen to China Great Wall Industry

Corporation.32 The same day, the complete Preliminary Report was

express-mailed by Yen to the Independent Review Committee members.33

On May 13, Yen also faxed the Preliminary Report to a hotel in Beijing

for Paul O'Connor of J&H Marsh & McLennan, who was a guest

there.34

None of these transmitted documents was submitted to the U.S.

Government for review prior to its transmission to the PRC.35

Defense

Department Analyst Discovers the Activities

of the Independent Review

Committee

The May 13-19, 1996, issue of Space News, a widely-read industry

publication, contained an article stating that Wah Lim, as Chairman of the

Independent Review Committee, had faxed the committee's report of the

failure review to the PRC.36

On or about May 14, 1996, Robert Kovac, an Export Analyst in the

Defense Department's Defense Technology Security Administration (DTSA),

read the Space News article and became concerned that the Independent

Review Committee's activities were not conducted under a license. Kovac

was particularly alarmed that, according to the article, a failure review

report had been distributed to the PRC.

Kovac immediately acted on his concern. He called Loral's Washington

representative and asked whether the Independent Review Committee's

activities had been conducted under a license. Loral's response was to

propose a meeting with Kovac and others for the following day.

On May 15, 1996, Loral's Export Control Officer met with licensing

personnel at the State Department and the Defense Department to report on

the Independent Review Committee's activities.

The Defense Department advised

the Loral officials to halt all Independent Review Committee activity

and consider submitting a "voluntary" disclosure to the State

Department.

The State Department made similar recommendations, and sent letters to

both Loral and Hughes soon afterward that reported that the State

Department had reason to believe that the companies may have participated

in serious violations of the International Traffic in Arms

Regulations.

The State Department also requested that the companies immediately

cease all related activity that might require approval, provide a full

disclosure, and enumerate all releases of information that should have

been controlled under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations.

Loral and

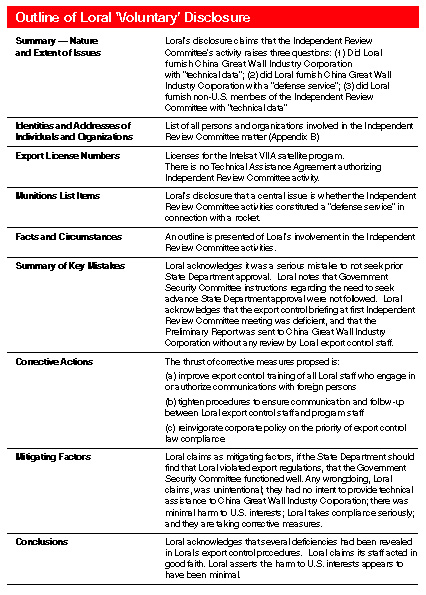

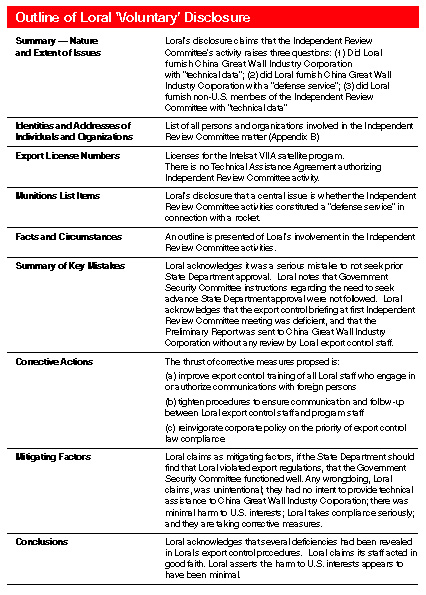

Hughes Investigate the Matter

On May 23, 1996, Loral engaged the law firm of Feith & Zell of

Washington, D.C., to conduct a limited investigation, as counsel for

Loral, of the events related to the Independent Review Committee. That

investigation included document collection and review, and interviews of

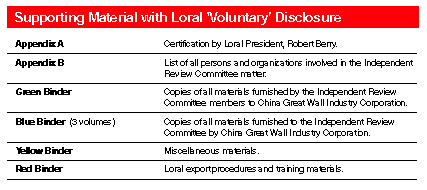

Loral employees. On June 17, 1996, a "voluntary" disclosure was submitted

to the State Department by Feith & Zell on behalf of Loral.37

In that disclosure, Loral stated that its procedures for implementing

export control laws and regulations were deficient, but that Loral was

implementing corrective measures. Also, Loral's disclosure concluded that

"Loral personnel were acting in good faith and that harm to U.S. interests

appears to have been minimal." 38

Hughes' General Counsel's office began an investigation into the

Independent Review Committee matter in early June 1996, after receiving

the State Department letter advising that Hughes may have been a party to

serious violations of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations.

Hughes' investigation report was submitted to the State Department on June

27, 1996. The Hughes report concluded that there was no unauthorized

export as a result of the participation of Hughes employees in the

Independent Review Committee.

The Hughes employees reportedly advised Loral employees to obtain the

appropriate State Department approvals prior to furnishing the documents

to the PRC.39

The Aftermath:

China Great Wall Industry Corporation Revises Its Findings on the Cause of

the Accident

In September 1996, China Great Wall Industry Corporation discarded its

original analysis, and in October 1996 made its final launch failure

presentation to officials at Loral.

China Great Wall Industry Corporation determined that the root cause of

the failure was a deterioration in the gold-aluminum wiring connections

within a power amplifier for the follow-up frame torque motor in the

inertial measurement unit. This was the very problem the Independent

Review Committee had identified in their meetings with PRC officials and

in the Preliminary Report.

U.S.

Government Assessments of the Independent Review Committee's Report, and

Referral to the Department of Justice

The materials submitted by both Loral and Hughes in their 1996

disclosures to the State Department were reviewed by several U.S.

Government offices, including the State Department, the Defense

Department, the Central Intelligence Agency, and an interagency review

team.

The 1997 Defense Department

assessment concluded that "Loral and Hughes committed a serious export

control violation by virtue of having performed a defense service

without a license . . . ."

Based on this assessment, the Defense Department recommended referral

of the matter to the Department of Justice for possible criminal

prosecution.

In July 1998, a U.S. Government interagency team conducted a review of

the Independent Review Committee's activities and reported the

following:

� The actual cause of the Long

March 3B failure may have been discovered more quickly by the PRC as a

result of the Independent Review Committee's report

� Advice given to the PRC by

the Independent Review Committee could reinforce or add vigor to the

PRC's design and test practices

� The Independent Review

Committee's advice could improve PRC rocket and missile

reliability

� The technical issue of

greatest concern was the exposure of the PRC to a Western diagnostic

process40

The interagency review also noted that the Long March 3B guidance

system on which Loral and Hughes provided advice is not a likely candidate

for use in future PRC intercontinental ballistic missiles. The Long March

3B guidance system is well suited for use on a rocket.

Details of the Failed Long March 3B-Intelsat

708 Launch and Independent Review

Committee Activities

The specific details of the events surrounding the Long March

3B-Intelsat 708 launch failure and the Independent Review Committee are

described in the remainder of this Chapter.

Background on

Intelsat and Loral

Intelsat

The International

Telecommunications Satellite Organization (Intelsat), headquartered in

Washington, D.C., is an international not-for-profit cooperative of 143

member nations and signatories that was founded in 1964. Intelsat is the

world's largest commercial satellite communications services provider. Its

global satellite systems bring video, Internet, and voice/data services to

users in more than 200 nations and on every continent.41

The member nations contribute capital in proportion to their relative

use of the Intelsat system, and receive a return on their investment.

Users pay a charge for all Intelsat services, depending on the type,

amount, and duration of the service. Any nation may use the Intelsat

system, whether or not it is a member. Intelsat operates as a wholesaler,

providing services to end-users through the Intelsat member in each

country. Some member nations have chosen to authorize several

organizations to provide Intelsat services within their countries.

Currently, Intelsat has more than 300 authorized customers.42

Intelsat includes two members

from the PRC: China Telecom is a signatory, and Hong Kong Telecom is an

investing entity. Their investment shares are 1.798 percent and 1.269

percent, respectively, giving the PRC a country total of 3.067 percent,

which makes it the eighth largest ranking member nation.43

On January 2, 1999, Intelsat had a fleet of 19 high-powered satellites

in geostationary orbit. These satellites include the Intelsat 5 and 5A,

Intelsat 6, Intelsat 7 and 7A, and the Intelsat 8 and 8A families of

satellites. The newest generation of Intelsat satellites, the Intelsat 9

series, is in production.44

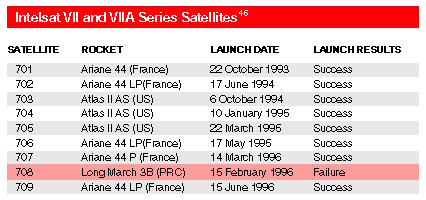

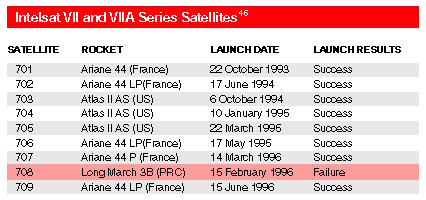

Nine satellites were manufactured in the Intelsat VII and VIIA series.

Loral manufactured this series of satellites, and they were launched

during the period from 1993 to 1996.45

Loral Space and

Communications

Loral Space and Communications, Ltd., is one of

the world's leading satellite communications companies and has substantial

interests in the manufacture and operation of geosynchronous and

low-earth-orbit satellite systems. The company is headquartered in New

York City and is listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Bernard Schwartz

is its Chairman. The company employs approximately 4,000 people.47

Loral Space and Communications, Ltd., owns Space Systems/Loral, one of

the world's leading manufacturers of space systems. It also leads an

international joint venture for the Globalstar system of satellites that

is expected to be placed in service in 1999. Globalstar will support

digital telephone service to handheld and fixed terminals worldwide. Loral

Space and Communications, Ltd., together with its partners, will act as

the Globalstar service provider in Canada, Brazil, and Mexico. Together

with Qualcomm, it holds the exclusive rights to provide in-flight phone

service using Globalstar in the United States. Loral Skynet, acquired from

AT&T in March 1997, is a leading domestic satellite service

provider.48

Space Systems/Loral

Space

Systems/Loral (Loral) designs, builds, and tests satellites, subsystems,

and payloads; provides orbital testing, launch services, and insurance

procurement; and manages mission operations from its Mission Control

Center in Palo Alto, California. Loral was formerly the Ford Aerospace and

Communications Corporation. In 1990, Ford Aerospace was acquired by a

group including Loral Space and Communications, Ltd., and re-named Space

Systems/Loral. Loral is located in Palo Alto, California, and Robert Berry

is its President.49

At the time of the Intelsat 708 failure, Loral was 51 percent owned by

Loral Space and Communications, Ltd. The remainder was owned equally by

four European aerospace and telecommunications companies: Aerospatiale,

Alcatel Espace, Alenia Spazio S.p.A., and Daimler-Benz Aerospace AG. In

1997, Loral Space and Communications, Ltd. acquired the foreign partners'

respective ownership interests in Loral.50

Loral is the leading supplier of satellites to Intelsat. Loral's other

significant customers include the PRC-controlled Asia Pacific

Telecommunications Satellite Co., Ltd., CD Radio, China Telecommunications

Broadcast Satellite Corporation, Globalstar, Japan's Ministry of

Transport, Mabuhay Philippines Satellite Corporation, MCI/News Corp., the

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration, PanAmSat, Skynet, and TCI. Loral employs

approximately 3,100 people, has annual sales of approximately $1.4

billion, and has a backlog of orders for approximately 80

satellites.51

Intelsat 708 Launch Program

On April 24, 1992, Intelsat awarded a contract to China Great

Wall Industry Corporation for the launch of Intelsat VIIA satellites into

geosynchronous transfer orbit.52

On or about September 18, 1992, the State Department issued a license

to Loral for the export to the PRC of technical data in support of

technical discussions for the launch of an Intelsat VIIA satellite.53 On

or about July 14, 1993, the State Department issued an export license to

Loral for the export of the Intelsat VIIA (708) satellite and associated

equipment necessary for the launch.54

Sometime in 1994, representatives from Intelsat and Loral performed a

site survey at the Xichang launch facility in the PRC. One of the Intelsat

representatives who was involved in the launch described the facility as

"primitive but workable."

On or about January 11, 1996, the Intelsat 708 satellite was shipped to

Xichang.

The Intelsat

708 Launch Failure

On February 15, 1996, at

approximately 3:00 a.m. local time, a PRC-manufactured Long March 3B

rocket carrying the Intelsat 708 satellite crashed into a mountain side

approximately 22 seconds after liftoff from the Xichang launch site. 55

Employees and family members of Loral witnessed the launch failure from

Palo Alto through a video feed from the launch site.56

Members of the Intelsat and Loral team in the PRC were not allowed by

PRC officials to visit the rocket debris field until late in the afternoon

of that same day.

At least three different explanations have been offered as to why the

Loral and Intelsat employees were not allowed onto the debris field for

approximately 12 hours:

� The first explanation was

that Loral and Intelsat employees were kept away from the debris field

until safety hazards from the crash site could be neutralized

� The second, as reported in

the news media, was that the delay had been imposed to give PRC

officials time to seek out U.S. satellite encryption devices intended to

protect the satellite command processor from unauthorized messages once

the satellite was in orbit57

� The third explanation,

offered by at least one Loral employee, was that the time delay gave

the PRC an opportunity to clean up the probable human carnage that

resulted from the crash

Once they were allowed to go to the site, members of the Loral team

began collecting and separating satellite debris from the rocket debris. A

rough inventory was done, and the satellite debris subsequently was crated

and shipped back to Loral in Palo Alto for analysis.58

Upon examination by Loral engineers in Palo Alto, it was determined

that the satellite's encryption devices had not, in fact, been recovered

from the crash site.

Events Leading Up to the Creation of

the Independent Review Committee

On or about February 27, 1996,

two weeks after the failure, PRC engineers announced that they believed

that the cause of the Intelsat 708 launch failure was the inertial

platform of the control system.59 This information was made public in an

attempt to demonstrate that the PRC had identified the cause of the launch

failure.

The interested parties included the aerospace industry in general, but

particularly Loral, Hughes Space and Communications Corporation (Hughes),

and the space launch insurance industry.

Hughes was scheduled to launch its Apstar 1A satellite on a Long March

3 rocket on or about April 1, 1996, less than two months after the

Intelsat 708 crash. Even though the Apstar 1A satellite was scheduled for

a different rocket, concern was still high in the insurance community.

On March 14, 1996, a meeting was held in Beijing involving Hughes; the

PRC-controlled Asia Pacific Telecommunications Satellite Co., Ltd., owner

of the Hughes-manufactured Apstar 1A; and the insurance underwriters for

the Apstar 1A.60

The main information the PRC

authorities, including the Asia Pacific Telecommunications Satellite

representatives, sought to convey to the insurance underwriters was

that their failure investigation relating to the Intelsat 708 launch had

shown the cause to be a failure of the inertial measurement unit.61 This

is the rocket subsystem that provides attitude, velocity, and position

measurements for guidance and control of the rocket.62

The PRC representatives stated that the inertial measurement unit used

on the Long March 3B that failed was different from the unit used on the

Long March 3, which was the rocket that would be used to launch the Apstar

1A. They concluded, therefore, that there should be no cause for concern

regarding the Apstar 1A launch.63

Nonetheless, representatives of the insurance underwriters stated that

insurance on the Apstar 1A launch would be conditioned on delivery of a

final report on the root causes of the Long March 3B failure and a review

of that report by an independent oversight team.64

Paul O'Connor, Vice President of J&H Marsh & McLennan space

insurance brokerage firm, later reported to Feith & Zell, a law firm

representing Loral on possible export violations, that insurers had paid

out almost $500 million in claims involving prior PRC launch failures, and

wanted the PRC to provide full disclosure about the cause of the Intelsat

708 failure.65

From April 10 through 12, 1996,

China Great Wall Industry Corporation held a meeting in Beijing concerning

the Long March 3B failure investigation.66 Loral sent three engineers

to the meeting: Dr. Wah Lim, Vice President and General Manager of

Manufacturing; Nick Yen, Integration Manager, Intelsat 708 Program; and

Nabeeh Totah, Manager of Structural Systems.67 Intelsat sent as its

representative, Terry Edwards, Manager of Intelsat's Launch Vehicle

Program Office. China Great Wall Industry Corporation provided Intelsat

and Loral with three volumes of data and eight detailed reports on the

current status of the failure investigation. The PRC's Long March 3B

Failure Analysis Team presented the failure investigation progress, and

the preliminary results up to that date, to Intelsat and Loral.68

On or about April 10, 1996, Bansang Lee, Loral's representative in the

PRC, on behalf of China Great Wall Industry Corporation, asked Lim to be

the Chairman of an independent oversight committee.

On or about April 10, 1996, Lim telephoned Robert Berry, Loral's

President, from the PRC. Lim reportedly told Berry that representatives of

China Great Wall Industry Corporation had asked him to chair an

independent oversight committee reviewing the PRC analysis of the Intelsat

708 launch failure.69

Berry says he gave permission for Lim to act as the chairman of the

independent oversight committee because of serious safety issues

associated with the PRC launch site that had been brought to his attention

after the Intelsat 708 failure.70

Before leaving Beijing, Lim created a charter for the committee, and he

changed its name to the "Independent Review Committee." 71 Eventually, the

Independent Review Committee was constituted with the following members

and staff:

The Government Security Committee

Meeting at Loral

On April 11, 1996, a quarterly Government

Security Committee meeting was held at Loral.73

The Government Security Committee was established by Loral in

cooperation with the Department of Defense in 1991, when 49% of Loral's

stock was owned by foreign investors.74 The express purpose of the

Government Security Committee was to monitor Loral's practices and

procedures for protecting classified information and technology controlled

under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations.75

The meeting attendees recounted to the Select Committee that Loral

President Berry arrived at the April 11 Government Security Committee

meeting after most of the others had gathered for it.76 Berry announced at

that time that he had just finished with a telephone call from Lim (in the

PRC) and had given Lim the authority to chair the Independent Review

Committee.77

According to Berry, he told the meeting that Lim had advised him that

the PRC was interested in Lim chairing the Independent Review Committee.

Berry testified that he approved Lim's request to participate during that

telephone conversation. Berry testified that he was aware that a report

would be prepared and distributed to the PRC and insurance companies.

However, he had an understanding with Lim that the report would not

contain any technical data or technical assistance.78 A discussion among

the meeting attendees ensued.

The minutes reflect that Dr.

Stephen Bryen, an outside member of the Government Security Committee,

recommended that "any report prepared as a result of [Loral's]

participation in the failure review be submitted to the State Department

prior to dissemination to the Chinese." 79

Bryen testified that he was disturbed by the idea of a failure

investigation involving the PRC, and that this would involve technology

transfer which required State Department approval. Bryen testified that

there was a lot of discussion on the matter, but all agreed that nothing

would happen without State Department approval.80

Duncan Reynard, Loral's Export Control Manager, recalls that Bryen

said:

You know, if there's anything written generated by this group of

people, you should run it by ODTC [Office of Defense Trade Controls,

Department of State] before you release it.81

Reynard says Loral Technology Transfer Control Manager William

Schweickert, Loral General Counsel and Vice President Julie Bannerman, and

he attended the Government Security Committee meeting. All three agreed

with Bryen's statement. Reynard says that he felt some responsibility in

connection with Bryen's comment; however, there was no indication from

anyone that a report was going to be prepared. Reynard says that if he had

known that a report was going to be prepared, with the intention of

disseminating it to foreigners, Loral would have sought the appropriate

U.S. Government approval.82

Reynard says that neither he, as Export Control Manager, nor Bannerman,

the General Counsel, nor Schweickert, the Technology Control Manager, took

any proactive measures to follow up on this matter.

Reynard says that "we didn't know what was happening - we didn't - we

were waiting for somebody to tell us." 83 According to interview notes of

Reynard prepared by an attorney from Loral's outside counsel, Feith &

Zell, Reynard said that no one asked him to look into the matter raised by

Dr. Bryen.84

Loral's General Counsel, Julie

Bannerman, testified that no one conducted any research to determine

whether the intended activities of the Independent Review Committee were

legal, or within Loral's company policy. Bannerman also testified that the

primary responsibility for matters relating to Bryen's statements would

have rested with Loral's export control office, namely Reynard and

Schweickert.85

Even though there was a formal mechanism for assigning action items in

Government Security Committee meetings, no action item was generated at

the April 11 meeting in connection with the Independent Review Committee.

No one was assigned to inform Lim of the Government Security Committee's

decision that Loral's participation in the Independent Review Committee

needed to be approved by the Department of State.86

One of the participants at the Government Security Committee meeting

was Steve Zurian of Trident Data Systems. Zurian says that Trident has

been a security advisor to Loral for nine years and provides export

consulting to the company. Trident's responsibilities include attending

the Government Security Committee meetings, taking notes, and drafting the

minutes. Zurian says that he and Caroline Rodine, another Trident

employee, attended the April 11, 1996, and the July 11, 1996, Government

Security Committee meetings.

Zurian says that it was the consensus of the attendees at the April 11,

1996, Government Security Committee meeting that Loral should seek and

obtain approval from the Department of State before participating in the

Independent Review Committee, and that Loral President Berry agreed with

the decision.

Zurian says that at the July 11,

1996, Government Security Committee meeting, Berry said that Loral had

followed up on Bryen's recommendation to obtain State Department

approval to participate in the Independent Review Committee. (As Loral

admitted in its June 27, 1996 disclosure to the Department of State,

however, this was not the case.)87

Zurian's draft of the July 11, 1996, meeting minutes reflects Berry's

remarks about obtaining State Department approval. Zurian says that he and

Rodine reviewed their notes of the meeting, specifically regarding Berry's

remarks, and both agree that the draft minutes are accurate.

Zurian says that it is possible that Loral's management failed to tell

Berry that they had not obtained the appropriate State Department

approval. He attributes Berry's erroneous understanding to his staff's

failure to advise him of the facts.

But numerous Loral personnel, including Berry, Bannerman, and Reynard,

were aware of Loral's deliberations with the Department of State regarding

the limits on Loral's participation in PRC failure analyses.88

On April 3, 1996, for example, Loral proposed to the State Department

certain language that restricted Loral's participation in possible failure

analyses in connection with two upcoming Long March launches from the PRC,

for the Mabuhay and Apstar satellites. Loral's proposal was that it would

not comment or ask questions in the course of those failure

analyses.89

It also should be noted that on or about January 24, 1996, a few weeks

prior to the Intelsat 708 failure, Loral received and reviewed the Apstar

technical data export license, which stated:

Delete any discussion or release under this license of any

technical data concerning launch vehicle [rocket] failure analysis or

investigation.90

On or about February 22, 1996, a week after the Intelsat 708 failure,

Loral received and reviewed the Mabuhay technical data export license that

also stated:

Delete any discussion or release under this license of any

technical data concerning launch vehicle [rocket] failure analysis or

investigation.91

The Apstar 1A

Insurance Meeting

On April 15 and 16, 1996, a meeting of representatives of companies

providing reinsurance for the upcoming Apstar 1A satellite launch took

place in Beijing. The Apstar 1A launch, and the issues arising from the

Long March 3B rocket failure, were discussed. The launch failure

presentations by PRC representatives made substantially the same points as

had been made at the March 14, 1996, meeting: that the Long March 3B

failure was due to the inertial measurement unit, and that this was not a

concern for the Apstar 1A launch because it would be launched by a Long

March 3 rocket utilizing a different inertial measurement unit with a

previous record of successful launches.92

At the same meeting, in response

to the requirement that had been stated by the insurance underwriters

at the March 14 Beijing meeting, the PRC representatives announced the

creation of an independent oversight committee (shortly thereafter named

the Independent Review Committee) to review the findings and

recommendations of the PRC's failure investigation.93

Wah Lim and Nick Yen of Loral, the designated Chairman and Secretary of

the Independent Review Committee, were present at the meeting and

discussed the role of the committee and its members. The two prospective

members from Hughes - John Smay, the company's Chief Technologist, and

Robert Steinhauer, its Chief Scientist - were also present, as was Nabeeh

Totah of Loral, who would serve as one of four Loral technical staff

members to the Independent Review Committee.94

During the April 15 and 16 insurers' meeting, the participants were

taken on a tour of the Long March rocket assembly area. They were also

shown, in a partially opened state, units described by the PRC as the

older Long March 3 inertial measurement unit and the newer Long March 3B

inertial measurement unit. Thus, almost half of the Independent Review

Committee participants had exposure at this time to the findings and views

of the PRC derived from their failure investigation, prior to the first

official Independent Review Committee meeting.95

On April 17, 1996, Wah Lim sent a letter to all Independent Review

Committee members and to China Great Wall Industry Corporation, confirming

that the first meeting of the committee would be in Palo Alto, California

from April 22 to 24, 1996.

The April 1996

Independent Review Committee

Meetings in Palo Alto

Meeting on April 22, 1996

On April 22, 1996, the first Independent Review Committee meeting

convened at Loral in Palo Alto. The foreign committee members, John Holt

and Reinhard Hildebrandt, were not present. No PRC officials were present,

due to a delay caused by visa problems.

Wah Lim called the meeting to order, and the meeting began without a

technology transfer briefing.

The matter of a technology transfer briefing was subsequently raised,

which prompted Lim to leave the meeting. Approximately ten minutes later,

William Schweickert, Loral's Technology Control Manager, arrived and

provided a technology export briefing to the Independent Review Committee

members who were present. According to one of the participants, it

appeared that Schweickert gave a presentation concerning the rules that

should be followed at a PRC launch site, rather than a briefing covering

technical data exchanges.

Schweickert provided the Independent Review Committee members with a

three-page technology export briefing.96 Schweickert says that he had

never prepared a briefing for a failure review before. Thus, he says he

used the export licenses for the launch of the Intelsat 708 as a basis for

the briefing. (Schweickert says that he learned about the imminent arrival

of the PRC visitors only a few days earlier.) However, according to notes

of an interview of Schweickert prepared by an attorney from Feith &

Zell, Loral's outside attorneys, Schweickert looked at the licenses

relating to the Mabuhay and Apstar IIR satellite programs for assistance

in preparing the Independent Review Committee briefing. Those licenses

were more current than the Intelsat 708 license issued in 1992.

Schweickert stated that these two

licenses required the presence of Defense Department monitors during any

discussions with the PRC. He said he knew Defense Department monitors

would not be present at the Independent Review Committee meeting. As a

result, he said, he would have to be "careful" in preparing his export

briefing. Schweickert also said that there was not enough time to get a

license.

Schweickert told the Independent Review Committee members that Loral

did not have a license for the meeting. According to Schweickert, he

discussed what he thought the Independent Review Committee could do

without a license - such as receive technical information from China Great

Wall Industry Corporation, request clarification of certain items, ask

questions, and indicate acceptance or rejection of the PRC's

conclusions.

Schweickert did not attend any of the Independent Review Committee

meetings, other than to give the briefing on the first day.

Duncan Reynard, Loral's Export Control Manager, did not learn of the

Independent Review Committee meeting on April 22, 1996 until Schweickert

told him that same day. Reynard says that Schweickert told him he had

prepared a briefing for the meeting, and he asked Reynard to review it.

According to interview notes of Reynard prepared by an attorney from Feith

& Zell, Reynard did not see Schweickert's briefing until late in the

day on April 22, 1996.97 Reynard says he reviewed Schweickert's briefing

and said it was "okay." 98

Reynard says he was not surprised to find out that PRC representatives

would be visiting Loral. Reynard says he "assumed the briefing and the

people that would normally attend something like that were knowledgeable

enough to know how to handle that kind of a meeting." 99

Reynard also says that his understanding of the meeting was that the

PRC representatives were going to make a presentation concerning their

failure investigation of the Intelsat 708 satellite.100

It should be noted that, during this first Independent Review Committee

meeting at Loral's offices, Loral's President, Executive Vice President,

and Export Control Manager were all absent. They had traveled to Europe in

connection with an unrelated business trip, and for vacation.101

The Independent Review Committee members who were present spent the

first day at Palo Alto reviewing the PRC failure analysis. The documents

consisted of approximately 14 reports dealing with technical material,

analysis, and failure modes.102

Meeting on April 23, 1996

On April 23, 1996, the two foreign members of the Independent Review

Committee and the PRC engineers arrived at Loral. The PRC representatives

included:

� Huang Zouyi, China Great

Wall Industry Corporation

� Professor Chang Yang,

Beijing Control Device Institute

� Li Dong, China Academy of

Launch Vehicle Technology

� Shao Chunwu, China

Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology103

The majority of this second day was spent trying to understand the PRC

failure investigation. Many Independent Review Committee members say there

was difficulty in understanding the PRC representatives' presentation

because of language problems. As a result, many clarifying questions were

asked of the PRC representatives. However, Feith & Zell interview

notes of one Independent Review Committee member specifically stated that

a "good translator" was present at that meeting.

The PRC officials stated that they believed the failure mode was

located in the inertial guidance system of the Long March 3B rocket.104

Specifically, they believed the failure was caused by a break in a wire to

a torque motor controlling the inner gimbal in the inertial measurement

unit. While the Independent Review Committee members told the PRC

representatives that they did not necessarily disagree with this analysis,

the minutes of the Palo Alto meeting reflect that the committee

recommended additional investigation by the PRC to verify its failure

analysis.105

During the meeting, the PRC representatives presented information about

the Long March 3B rocket design. The Independent Review Committee members

asked questions to better understand the technology used by the PRC, as it

was not as advanced as Western designs. Hughes Chief Scientist Robert

Steinhauer described the afternoon session as a "tutorial." 106

Meeting on April 24, 1996

On

April 24, 1996, the PRC representatives attempted to answer some of the

questions presented by the Independent Review Committee on the previous

day. There was also continued discussion of the launch failure analysis,

and plans were made to continue the meeting in Beijing on April 30 and May

1, 1996.107

The Hughes committee members, Steinhauer and Smay, did not attend the

meeting on April 24.108

The following is the agenda for the April 24 Palo Alto Independent

Review Committee meeting:

9:00 AM REVIEW OF PROGRESS TO DATE IRC

9:30 AM REVIEW OF LM-3/LM-3B

DIFFERENCES CGWIC

10:30 AM BREAK

10:45 AM CONTINUE REVIEW OF

LM-3/LM-3B CGWIC

12:00 PM LUNCH

1:00 PM ACTION ITEMS FOR LM-3/APSTAR

1A IRC

3:00 PM BREAK

3:15 PM WRAP UP AND PREPARATION FOR BEIJING

MEETING IRC

4:00 PM OPEN DISCUSSION ALL

5:00 PM END

United States

Trade Representative Meeting on April 23, 1996

On April 23, 1996, Nick Yen, Loral's Intelsat 708 Launch Operations

Manager and Secretary of the Independent Review Committee, and Rex Hollis,

an employee in Loral's Washington, D.C. office, met with various U.S.

Government officials at the offices of the U.S. Trade Representative in

Washington, D.C.

In a memorandum prepared by Yen dated May 15, 1996, memorializing this

April 23, 1996 meeting, Yen described the purpose of the meeting as an

informal briefing on the activities leading up to and including the launch

failure.109

According to Yen's memorandum,

the U.S. Government representatives at the meeting were interested in the

accuracy of claims by the PRC authorities about the extent of the damage

caused to a nearby village by the rocket's explosion. They were also

interested in the course of action that was being taken to correct safety

problems and deficiencies at the launch site.

According to the memorandum, which was prepared after the State

Department inquiries about possible export violations by Loral and three

weeks after the meeting, Yen mentioned that an independent review

committee headed by Wah Lim had been created.110

The memorandum reflected that Yen told the meeting attendees that,

since launch site safety related to how the rocket behaves, the

Independent Review Committee would review the findings, conclusions, and

corrective actions performed by the PRC Failure Investigation Committee,

and set the necessary safety implementation requirements for China Great

Wall Industry Corporation to consider for its future customers, not just

Loral.111

Yen did not tell the attendees that Loral did not have a license to

participate in the investigation.

The memorandum stated that one of the U.S. Trade Representative

officials, Don Eiss, requested a copy of the Independent Review Committee

formal report when it became available. According to the memorandum, Yen

told Eiss that he would have to consult with Lim prior to the

dissemination of the report. There is no indication that the report was

ever disseminated to any of these U.S. Government representatives. The

memorandum reflected no substantive discussion concerning the Independent

Review Committee report.112

The meeting was not about export licensing for failure analyses, and no

U.S. official at this meeting has been identified as an export licensing

officer. Loral, in its Voluntary Disclosure, admitted that:

[T]his meeting cannot be taken as U.S. government consent to

Loral's activities on the IRC (particularly as the State Department

personnel were not from the Office of Defense Trade

Controls).113

The April and

May 1996

Independent Review Committee Meetings in

Beijing

Meeting on April 30, 1996

On

April 30, 1996, the second series of Independent Review Committee meetings

convened, this time in Beijing. Hughes committee member Robert Steinhauer

did not attend this meeting. The committee members stayed at the China

World Hotel, and were transported by van from their hotel to the meeting

location.

The meeting was held in a large room in a building on the China Great

Wall Industry Corporation campus. In attendance were representatives from

various PRC aerospace organizations.

According to Independent Review Committee members, various PRC

representatives made presentations concerning different aspects of their

launch failure investigation.

Many of the committee members say that it was difficult to understand

parts of the presentation. In some instances, the presentations were made

in Chinese and interpreted for the committee members. Some of the

committee members say that, in their opinion, the interpreters did not

have technical backgrounds. According to some of the committee members who

testified, this lack of technical training contributed to the difficulty

in understanding the PRC presentations.

Members' Caucus at the China World

Hotel

On the evening of the first day, the Independent Review

Committee members and technical staff held a caucus in a meeting room at

the China World Hotel. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the

presentations that had been made by the PRC, to consider the possible

causes of the launch failure, and to decide on what to present to the PRC

participants the following day.

The caucus meeting ran from about 7:00 p.m. to at least 10:00 p.m. No

PRC personnel were present. However, according to testimony presented to

the Select Committee, the discussion was almost certainly secretly

recorded by the PRC.

Topics of discussion included, among others:

� Proposed failure

modes

� Redundancy

� High fidelity testing

� Gimbals

� Gyroscopes

� Torque motors

� Telemetry data

� The oscillatory behavior of

the flight

During the caucus, the Independent Review Committee members expressed

views that were incorporated in attachment IV of their Preliminary Report.

One committee member described the meeting as a "brainstorming"

session.

The same member stated, "I'm sure we felt that we had to get together

and try to summarize and understand and agree among ourselves what we

thought we had heard and seen that day, and that was the whole idea . . .

It gave us a chance to talk among ourselves and review what we had heard

and perhaps raise questions."

Striking is one Independent

Review Committee member's admission that there were probably things

said in these supposedly closed meetings of the committee that they would

not have said in front of the PRC officials.

According to a document reflecting discussions in the caucus meeting,

the Independent Review Committee members were focusing on the following

failure modes:

� Broken wires in general, as

postulated by the China Academy of Launch Technology

� Frozen follow-up gimbals, a

failure mode not considered by the PRC

� Open loop in the feed back

path114

As early as February 29, 1996, China Great Wall Industry Corporation

had identified that there was a problem with the inertial platform.115 In

a March 28, 1996, Information Release from China Great Wall Industry

Corporation, the PRC announced that they were one experiment away from

completing the simulation experiments on the Long March 3B failure

scenarios.116 The Information Release stated that they had analyzed the

telemetry data and the failure mechanism. Through this analysis, they had

isolated four inertial platform failure modes:

� A broken wire to the torque

motor for the inner frame

� A blocking of the inner frame

axis

� An open loop of the follow-up

frame

� Environmental

stress

From its analysis of the telemetry data, China Great Wall Industry

Corporation determined that during the 22-second flight of the Long March

3B, there were three distinct cycles, each of which lasted a little over

seven seconds. Witnesses at the launch confirmed that the rocket veered

three times before impact. China Great Wall Industry Corporation theorized

that the rocket veered as the result of a faulty wire (or flawed solder

joint) in the inertial platform, which intermittently disconnected and

reconnected at the end of each of the three cycles.117

By the time of the Beijing

insurance meeting on April 15, 1996, China Great Wall Industry

Corporation had eliminated two of the four failure modes identified in

March. Specifically, they isolated the problem to the inner frame and

posed the following possibilities:

� Electrical circuitry

problems: open loop through the inner frame; broken wire; poor

contact; or false welding

� Mechanical problems: the

axis of inner frame clamping; foreign object blocking118

Viewgraphs supplementing their report stated that the inertial platform

veered three times during the 22-second flight, and that the first

periodic motion occurred in the torque motor on the inner frame axle of

the platform.119 China Great Wall Industry Corporation presented similar

information to the Independent Review Committee participants at the first

meeting of the committee in Palo Alto from April 22 to 24, 1996.

At the second Independent Review Committee meeting in Beijing, China

Great Wall Industry Corporation continued to emphasize the inner frame as

the problem. In fact, they provided the Independent Review Committee

participants a failure tree that specifically eliminated all but the inner

frame as a potential failure mode.120

In the words of one Independent Review Committee participant, "I think

if they had not had the IRC, they would have sold that one down the

line."

The Independent Review Committee

was not convinced. First, several committee participants thought the

disconnecting and reconnecting wire theory either was not plausible or was

"highly unlikely." In addition, China Great Wall Industry Corporation was

only able to replicate the first seven to eight seconds of the flight,

rather than the full 22-second flight. Finally, China Great Wall Industry

Corporation had not resolved a fundamental question as to why the

telemetry data in the follower frame was flat, rather than

oscillating.121

In a continuing effort to persuade China Great Wall Industry

Corporation to explain the behavior of the full 22 seconds of flight, the

Independent Review Committee provided comments to the PRC after the first

day of the Beijing meeting. The Independent Review Committee stated that

"China Academy of Launch Technology should consider to perform a

simulation test using an open feed back path as the initial condition. It

is also very critical for CALT [China Academy of Launch Technology] to

explain why the follow-up gimbal resolve[r] (angle sensor) stayed flat

throughout the flight." 122

While the Independent Review Committee generally acknowledged China

Great Wall Industry Corporation's proposed failure modes, they did so only

after modification. For example, the PRC proposed a "broken wire to the

torque motor for the inner frame," while the Independent Review Committee

proposed a "broken wire in general as postulated by CALT." While the PRC

proposed a "blocking of the inner frame axis," the Independent Review

Committee proposed "frozen follow-up gimbals." 123

Meeting on May 1, 1996

May

1, 1996, was the second day of the Independent Review Committee Beijing

meetings. The following is the agenda for the second day's of that

meeting:

8:20 IRC MEMBERS LEAVE HOTEL CGWIC

9:00 IRC'S REVIEW TO THE ANSWERS

IRC 11:00 DETAILED DISCUSSIONS OF LM-3 AND LM-3B FAILURE ALL ISOLATION

ANALYSIS AND IMU FOR LM-3 & LM-3B MANUFACTURING AND TEST PROCEDURE

ETC.

12:00 LUNCH BREAK (BUFFET)

13:00 TOUR OF THE ASSEMBLY WORKSHOP

OF L/V, THE IMU TEST FACILITY ALL

16:00 WRAP UP SESSION

IRC/CGWIC

17:00 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS TO DATE AND CONCLUSION IF AVAILABLE

IRC

19:00 DINNER HOSTED BY CASC

During the morning session, a "splinter meeting" was held to

specifically discuss the inertial platform. The meeting was attended by

the five Independent Review Committee members, and a small group of PRC

engineers.124 During the meeting, the committee participants sought

clarifications concerning the signal flow diagrams in order to determine

the cause of the open circuit.

During the Independent Review Committee meetings in Beijing, several of

the Independent Review Committee members toured the PRC manufacturing and

assembly facilities for the Long March 3B inertial measurement unit.

During those tours, the Independent Review Committee members commented to

the PRC engineers about the quality control practices used by the PRC.

These comments on quality control were reiterated in the Independent

Review Committee Preliminary Report sent to China Great Wall Industry

Corporation on May 10, 1996.125

The

Independent Review Committee Preliminary Report

Writing the Report

Upon

completion of the Beijing Independent Review Committee meeting on May 1,

1996, the process of writing the report began. Wah Lim delegated the task

of writing the major portion of the report to John Holt, the British

committee participant, because he seemed to have the best understanding of

the issues related to the Long March 3B inertial measurement unit.126

On or about May 2, 1996, Holt faxed his draft summary to Nick Yen, the

Secretary of the Independent Review Committee, at Loral. Yen then

disseminated Holt's draft summary to the other Independent Review

Committee members. The committee members subsequently provided their

comments on Holt's draft to Yen and Lim.127

Loral Sends the Draft Report to the

PRC

Yen assimilated all of the material into a draft

Preliminary Report during the period May 2 to 6, 1996. He completed the

draft Preliminary Report around May 6 or 7, 1996. Yen then showed the

report to Loral's Wah Lim, the Chairman of the Independent Review

Committee. Lim suggested changes, and told Yen to send it to the

Independent Review Committee members, and to the China Great Wall Industry

Corporation.

On May 7, 1996, Yen distributed the draft Preliminary Report to the

Independent Review Committee members and technical staff for additional

comments.128

On the same day, Yen also faxed a copy of the draft to China Great Wall

Industry Corporation in the PRC.129

According to interview notes of Lim taken by a Feith & Zell

attorney, Lim acknowledged that he instructed Yen to send the draft

Independent Review Committee report to everyone, including the PRC, on May

7, 1996.130

It should be noted that Lim refused to be interviewed or deposed during

this investigation.

The Contents of the Draft

Report

The Independent Review Committee's Preliminary Report

repeated the committee's concerns that China Great Wall Industry

Corporation's conclusions were debatable. As a short-term recommendation,

the Independent Review Committee stated:

An explanation of the total flight behavior is essential to fully

confirm the failure mode.131 A mathematical numerical solution is

recommended immediately, to be followed by a hardware in the loop

simulation test when possible . . .132

In addition, the draft Preliminary Report documented the Independent

Review Committee's view that an intermittently reconnecting wire - the

PRC's theory - was not necessary for the rocket to behave in the manner in

which it did.

Specifically, the Independent Review Committee postulated that a single

disconnectionwithout reconnectionwould be "a much simpler, and

more plausible, explanation." 133

The Independent Review Committee repeated its concern that "the open

circuit could be at various other physical locations," suggesting that the

problem might not be in the inner frame,134 as was posited by the PRC.

The Independent Review Committee

participants questioned China Great Wall Industry Corporation's

assertions that the flat data from the follower frame were bad

data.135 They therefore requested that China Great Wall Industry

Corporation confirm that the follower frame had functioned properly during

flight.

Ten days after China Great Wall Industry Corporation received the

Independent Review Committee's Preliminary Report, it abandoned testing of

the inner frame, and started vigorously testing the follower frame.

One month later, China Great Wall Industry Corporation determined that

the cause of the failure was an open feed back path in the follower frame.

This finding was confirmed in a presentation by China Great Wall Industry

Corporation to Loral, Hughes, and others in October 1996.

In addition to these observations, the Independent Review Committee

document recommended that a "splinter" meeting be held the following day

to examine more closely the failure modes related to the inertial guidance

system of the Long March 3B.136 John Holt, John Smay, Jack Rodden, Fred

Chan, and Nick Yen were selected to participate in the meeting.137

Notification to Loral Officials That a

Report Had Been Prepared

On or about May 6, 1996, Lim spoke

during a Loral staff meeting about the work of the Independent Review

Committee, and mentioned that a report was going to be submitted to the

insurance companies on or about May 10, 1996.

Julie Bannerman, Loral's General Counsel, says that she was concerned

about the possibility that the company might incur some liability to the

insurance companies because Loral employees would be associated with

representations that were made in the report. Bannerman advises that, for

this reason, she wanted to add a disclaimer to the report.138

Thus, Bannerman believes that she asked Lim to provide her a copy of

the report prior to its dissemination, although she has no specific

recollection of making the request.139

Bannerman says she does not recall any mention at the Loral staff

meeting that the eport was being provided to the PRC.140

Loral Review and Analysis of the

Independent Review Committee Report

Loral General Counsel Julie

Bannerman says that she found a copy of the Independent Review Committee

draft Preliminary Report on her desk on May 9, 1996. She does not know who

put the document on her desk, but believes that it was probably Wah

Lim.141

Bannerman says that she looked at

the report and realized that it contained technical information she

did not understand. As a result of the concern this caused her from an

export control perspective, she says she began preparing a memorandum to

send to Loral's outside legal counsel, Feith & Zell in Washington,

D.C., for review.142

During the preparation of her memorandum, Bannerman says that she

telephoned Loral Export Control Manager William Schweickert because she

wanted to mention his April 22, 1996, export briefing in the memorandum.

Schweickert provided her with the requested information, which she

included in approximately one line in the memorandum, but she does not

recall whether she advised Schweickert that a draft report had been

prepared by the Independent Review Committee.143